Jean Best was about to resign from Rotary. It was a sad day for her: She loved being a Rotarian. But she had become enmeshed in a conflict with another member of her club.

Although she tried to engage with that member to defuse the situation, the problem persisted. Best could have pressed the issue, could have tried to run it all the way up the flagpole. But instead, she decided to back away.

She left that club and joined the Rotary Club of Newton Stewart, Scotland, where she’s very happy.

But she hasn’t given up on addressing the larger issue: “Now I’m looking at conflict resolution in Rotary clubs,” she says.

Some scientists who study the fossil record say that for much of history, people have dealt with conflict through violence. Some even theorize that our very ability to work as a team evolved out of our need to compete against other groups.

And while bench-clearing brawls may be rare at your Rotary club, that doesn’t mean your meetings always end in a chorus of “Kumbaya” — especially at a moment in history when the fractiousness of the world seems to seep into our lives in unexpected ways.

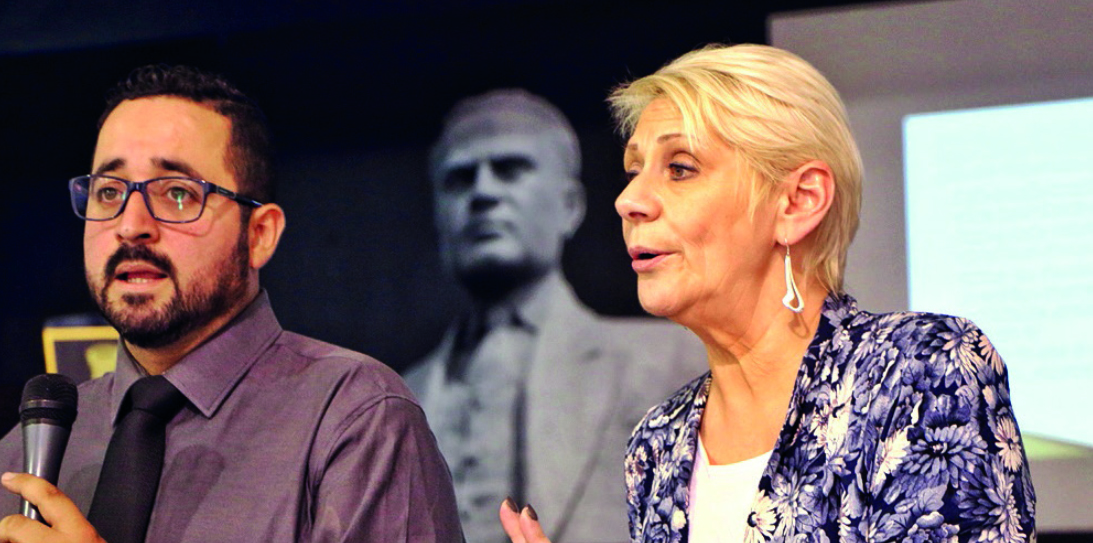

“The conflict in clubs is growing,” says Jo Pawley, 2019-20 governor of District 1020 (Scotland). “I’ve seen examples of bullying. I’ve seen people being downright rude. I’ve seen examples of people not leaving things alone, pulling the scab off something you think has been resolved.”

Calum Thomson, Pawley’s successor as district governor, agrees. “Every club’s got issues. They might be minor, minuscule, not that fundamental. But we’ve all got issues,” he says.

“It’s difficult to talk about conflict in clubs because many Rotarians don’t realise that there is conflict in clubs,” Best says. “So it’s about raising awareness to begin with about what a modern, 21st-century Rotary is all about.

“If we want Rotary to continue as the great organisation it is, we need to start changing the way we conduct our Rotary club meetings.

Conflict resolution is something we humans have been trying to master at least since the first Cro-Magnon tribal steering committee.

“It’s about clubs putting greater emphasis on how they discuss issues, rather than what they discuss. We found that people were leaving clubs because they were not listened to or were not spoken to appropriately.

“Talking and listening should be an important part of Rotary. Into this comes an awareness of bias, diversity, and stereotypes.”

Rotary clubs aren’t the only place where conflict occurs, of course. We live in an age of rage: road rage, air rage, office rage, bike rage, quarantine rage. Online, we’re subjected to Twitter fights, Facebook unfriendings, Nextdoor knockdowns, and LinkedIn lashings.

An entire field of study is dedicated to systematically learning how to ratchet down disagreements, cool emotions, and help everyone be happy with getting less than they wanted.

Conflict resolution isn’t something that was invented recently. It’s also not the exclusive province of Western diplomats and academics.

The European Union is a well-known “peace system,” but there’s also the Iroquois Great League of Peace and Power in New York, the tribes of the Upper Xingu River basin in Brazil, and the aboriginal tribes of the Western Desert in Australia.

Talking and listening should be an important part of Rotary. Into this comes an awareness of bias, diversity, and stereotypes.”

According to one study of what they all have in common, the impetus behind these systems was to manage conflict between neighbouring societies before it rose to the level of war.

Some employ what’s known as an active peace system, while others rely on passive systems that use avoidance and toleration. But how can we use the active system to address interpersonal conflicts, not just societal ones?

Best has developed a four-seminar programme to help keep meetings, Rotary club meetings included, moving along smoothly and openly.

“One of the watchwords we use is, ‘Get curious before you get furious,’” she says. “In other words, ask, ‘Why did you say that? Why did you do that?’ before you get angry.

“In a lot of cases, people just fly off the handle and walk out the door. It’s about saying, ‘Hang on a minute, let’s discuss this. Let’s open this up. Tell me why you feel like this. What have I said that’s upset you?’ It’s a way of defusing the situation.”

Rotary clubs aren’t the only place where conflict occurs, of course. We live in an age of rage: road rage, air rage, office rage, bike rage, quarantine rage. Online, we’re subjected to Twitter fights, Facebook unfriendings, Nextdoor knockdowns, and LinkedIn lashings.”

In 2020, Thomson and Pawley started working with Best to help train their district’s incoming club presidents in conflict resolution.

“It’s all about listening to people,” says Thomson. “And when they say something, you need to be able to repeat it back to them. So you’re saying, ‘I think this is what you said,’ so there are no misunderstandings and we both know what we’re talking about.”

“Jean has this brilliant test where you have to describe something but you can’t use nouns,” says Pawley. The test consists of two people sitting back to back, so neither one can see the other. One person has to draw what the other person is describing.

“What tends to happen is that you draw something completely not what was being described,” she says. “It shows you that your listening skills are not as good as you think they are. It shows that you have to listen more to what is actually being said.”

The exercise also shows the speakers how their words can be misinterpreted, so everyone involved learns how communication can go wrong.

Best has developed a four-seminar programme to help keep meetings, Rotary club meetings included, moving along smoothly and openly.

Best, who worked in education for nearly 40 years as a teacher, a head teacher, and finally as an inspector of schools for the Scottish government, makes this point too.

“People, especially older people, in Rotary think they know how to talk to each other,” she says, “but they actually don’t. They think they’re listening, and they’re not. And we prove to them that they don’t know how to talk and that they don’t know how to listen.”

Louisa Weinstein, a mediator who wrote a guide called ‘The 7 Principles of Conflict Resolution: How to Resolve Disputes, Defuse Difficult Situations and Reach Agreement’, agrees with this approach.

“The first, basic thing is to listen — to really listen, as a mirror to the other person,” she says.

“I might reflect back what the other person has said, and it might be absolutely to the letter what they said. And they may still come back to me and say, ‘No, no. I didn’t say that.’”

This happens because often we say things that we don’t mean or mean things that we don’t say. But an even bigger obstacle is that we all think we’re right.

People, especially older people, in Rotary think they know how to talk to each other,” she says, “but they actually don’t. “

“We need to assume a non-judgmental attitude,” says Weinstein. “If I’m going to resolve conflict, I need to be open to the fact that my judgment may not be valid, even if I think I’m absolutely right.

“Besides, being right isn’t necessarily going to help anyway. It’s about trying to understand, rather than to be understood.”

In Best’s system, once a conflict is out in the open, all parties offer ideas for resolution, which are dis-cussed and considered.

Finally, the person who has the conflict chooses the first step forward, followed by the others. This gives each party more ownership over the outcome.

As Best herself knows, this doesn’t always work. Still, it’s far better than just hoping a conflict will quietly disappear.

Arguments within clubs, she says, have resulted in more than a few members drop-ping out. “Quite often it’s because of something that’s been said, or someone hasn’t been listened to properly and then there’s no discussion,” she says.

“We can’t afford to do this. Rotary is too important to the world to lose Rotarians over silly disagreements.”

- This article is published in the current issue of Rotary magazine, published by Rotary International from Evanston.