It was 11.32 hours on November 6th, 1986, and I was the captain of the Chinook helicopter which crashed just two miles short of its destination, Sumburgh Airport in the Shetland Islands.

One passenger and I survived the crash. How or why we survived is a mystery. There is absolutely no explanation, just pure luck!

For a long time after the accident, I used to ask myself ‘Why were the other passengers not lucky?’ I guess nobody can answer that question.

When the helicopter wreckage was retrieved from the sea, the accident investigating inspector met me and wondered how I could have possibly survived and come out of it with very minor injuries.

I joined British Airways Helicopters in 1975 after leaving the Indian Air Force. In 1982 I converted on to Chinooks, the Boeing Vertol BV234, the biggest civilian helicopter in the world. By 1986, I had already flown over 2,500 hours on the Chinooks and loved every minute of it.

I had taken G-BWFC, Chinook helicopter, to Sumburgh for the week on Monday 3rd of November 1986.

It was 11.32 hours on November 6th, 1986, and I was the captain of the Chinook helicopter which crashed just two miles short of its destination, Sumburgh Airport in the Shetland Islands.”

We had two sets of crews flying to the Brent oil and gas fields in the East Shetland Basin, just over 100 nautical miles north-east of Sumburgh Airport.

First Officer Neville Nixon, my co-pilot, who was 43, had left Bristow Helicopters a few years earlier and given up flying to help his wife, Pauline, set up a chemist shop in York.

After three years, the shop was doing very well and he found that Pauline could manage the shop by herself. He loved flying and decided to come back to flying.

He joined British Airways Helicopters in the summer of 1986. Since Neville hadn’t flown for nearly three years, he was very keen to fly as much as possible.

On November 6th, he was rostered to do the afternoon shift. Since morning shift did two flights and the afternoon shift did only one, Neville had swapped his shift with First Officer Mike Stanley. Sadly for him, this shift change cost him his life.

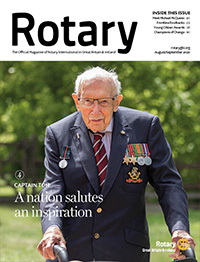

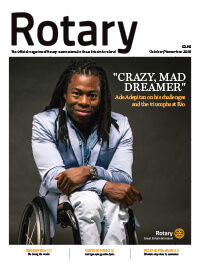

Pushp Vaid – pilot

Thursday, November 6th 1986, was a beautiful day at Sumburgh Airport. The wind was light and it didn’t feel cold.

I expected good flying conditions. Neville was already planning for our flight by the time I arrived that morning.

After finishing the planning, he rang up his home. That was the last time he spoke to his wife.

Mike Walton, our cabin attendant, arrived about 7.30am and went to do his checks on the helicopter. Checks included making sure that cabin was clean and all the safety equipment was on board.

Our original plan was to land at Brent Charlie and Brent Delta – one of four platforms extracting oil and gas in the North Sea. At the last minute we were given a load to drop at Brent Alpha also. This added about ten minutes to our trip.

These ten minutes became very important when we were returning to base. We crashed just two miles and two minutes short of our destination. Destiny? Yes.

The flight was uneventful and after landing at Brent Alpha, Charlie and Delta we set course back to Sumburgh at 10.43. We had a full complement of 44 passengers and three crew on board.

Neville was the handling pilot now, and I was doing all the paper work, plus the radio calls.

We climbed to 2,500 feet on our route back to Sumburgh. We flew in and out of clouds. The weather was very nice and we had a very pleasant flight. We talked about all sorts of things to pass the time. Neville told me about his brother who had been to India and had loved it there. All this time, our bevel ring gear in the front gear box was breaking up and we had no way of knowing of the looming disaster.

I discovered this later when I listened to the cockpit voice recorder at the Aircraft Accident Investigation Board’s workshop. I could hear the noise of the gear break up for the entire 30 minutes of the tape.

After finishing the planning, he rang up his home. That was the last time he spoke to his wife.”

About 3.5 nautical miles from the runway, we started hearing a whining noise which seemed to be getting louder. The noise did not sound dangerous. By now, we were only two minutes from landing, flying about 300 feet above the sea, and our speed was reducing below 100 knots.

I informed the control tower at Sumburgh that ‘Foxtrot Charlie’ was on finals and we were cleared to land. After informing us that the passengers were all ready for landing, our cabin attendant had opened the cabin door and closed it behind him. I don’t think he had a chance to sit down and strap himself.

A fraction of a second after he closed the door, at 11.32 to be exact, we heard a very loud bang. Suddenly the helicopter pitched up and was pointing vertically up and I could see the sky ahead of me. I had no time to give a May Day call.

We were falling backwards towards the North Sea. The helicopter, which had been travelling at about 100 knots, came to a sudden stop and was now pointing vertically up. Sadly, the whiplash effect killed at least half of the passengers.

At 11.32 to be exact, we heard a very loud bang. Suddenly the helicopter pitched up and was pointing vertically up and I could see the sky ahead of me. I had no time to give a May Day call.”

My co-pilot probably died at that moment. As the handling pilot, he was sitting without his back touching the backrest, with the result that the whiplash effect broke his neck. As the non-handling pilot, I had my back resting at the backrest. The whiplash effect on me was not as great, though thinking about it now, I start feeling the pain in my back.

I found out later that the whining noise was the front gear breaking up. It was then a matter of 20 to 30 seconds before the two counter rotating rotor blades hit each other – and that was the loud bang we heard.

The rear rotor blades were shaking so much that they, along with the gearbox, weighing more than a ton, parted company from the helicopter and splashed in the water about one nautical mile away from us.

One gentleman standing about five miles away on top of a hill, near Sumburgh Airport, saw our helicopter falling towards the sea and he actually pointed out to the salvage team where to look for the rear rotor blades. No, he didn’t have a video camera!

Pushp Vaid joined British Airways Helicopters in the summer of 1986.

Now there was no rear rotor. Nothing was holding the back end of the helicopter up. So the back fell and the nose was pointing up to the sky.

Sitting in the cockpit I could see the sky straight in front of me. I got the feeling we were going straight up. Instinctively I grabbed the cyclic control and pushed it all the way forward to level the helicopter. It appeared I had done an outside loop.

I felt negative G force when the helicopter seemed to move from pointing vertically up to vertically down. Now I could see the sea in front of me. It appeared the helicopter was now rushing nose-down, vertically towards the sea.

When I pushed the cyclic stick all the way forward, the front rotor blades, which were still responding to the controls, flipped the cockpit section of the helicopter over. This probably saved the two of us who did survive.

The whole helicopter was falling backwards towards the sea. The cockpit, which had tipped over and was still attached to the cabin at the floor, seemed to be going straight towards the sea. That also meant that there was a huge hole at the top of the cabin, where the cockpit had been. This is the hole which Eric Morrans, the other survivor, was thrown out of when he was unconscious under water.

While we were falling, I was aware that everything around me was breaking up. I was thinking double time to see if there was anything I could do to save the helicopter and all of us in it. It felt as if I was in a rollercoaster ride, wishfully thinking that at the bottom, the helicopter would roll out and we would land on the water and everybody would come out.

The whole helicopter was falling backwards towards the sea. The cockpit, which had tipped over and was still attached to the cabin at the floor, seemed to be going straight towards the sea.”

Strange, not for a moment did I think that anybody was going to die!

The front rotor blade had chopped off the part of windscreen in front of the co-pilot. Broken bits from the windscreen were hitting me on the face. The left side of my face was all cut up and my nose was broken. Amazingly nothing hit my eye.

When we hit the water, the rear end of the helicopter took all the impact. The rest of the passengers and our cabin attendant died on impact. No-one drowned.

The North Sea is pretty cold. The water temperature that day must have been around seven or eight degrees centigrade.

The cockpit, with me still in it, seemed to keep going down and down and down in the water. It must have gone down at least 30 feet below the surface, before it stopped moving.

I could see the sunlight and I knew which way I had to swim. However, when I left the seat and started to move I discovered that I was going the wrong way. It was getting darker.

I turned around and headed towards the sunlight. I passed through the emergency window, which had blown away on impact and swam towards the surface.

When we hit the water, the rear end of the helicopter took all the impact. The rest of the passengers and our cabin attendant died on impact. No-one drowned.”

Later I discovered that I had not even unbuckled my belt. When the cockpit was salvaged, we discovered that one strap had broken, but the other three were still in locked position. I have no idea how I came out of those straps.

It was a beautiful sunshine, which met me when I reached the surface. I was feeling very cold and was breathing very fast and hard. I saw what looked like a big bowl. I think it was part of the fuel tank cover. I managed to climb into it. But two seconds later a small wave tipped me over and I was back in the water.

I wasn’t worried; in the back of my mind I knew the rescue helicopter would be overhead in a few minutes. I was just waiting for them to come and pick me up. Then a body popped up next to me and then another and another.

There must have been at least seven bodies floating close to me. They were not moving or doing anything. That is the first time it occurred to me that perhaps some people were dead.

Then there was a lot of hydraulic fluid and broken pieces of the helicopter that were floating around in the sea near me. I could see broken pieces everywhere.

The retrieved Chinook helicopter

As soon as I saw the coastguard helicopter, I waved. The helicopter hovered over me, the winchman came down, put a strap around me and winched me up.

Only one passenger, 20-year-old Eric Morrans, survived the crash. He was sitting in the front row of seats, which faces backwards. He was facing the 42 passengers and he saw the fear of death in their faces when the helicopter was plunging vertically backwards into the sea.

Eric was just plain lucky like me. Instinctively, he zipped up his survival suit when he heard the big bang. There were a lot of broken pieces flying around in the cabin and he was rendered unconscious.

When the helicopter plunged into the water, Eric went with it. However, when he was about 30 feet under water, his survival suit, which was full of air, acted like a football under water, and threw him out through the hole behind him and towards the surface.

Only one passenger, 20-year-old Eric Morrans, survived the crash. He was sitting in the front row of seats, which faces backwards. He was facing the 42 passengers and he saw the fear of death in their faces.”

A wave crashed over Eric’s face and woke him up and luckily, as his eyes opened, one dinghy inflated just next to him. Eric heard the helicopter overhead and saw me being winched up. He was worried he might be left behind and started waving frantically. He was winched up after me.

We were now both aboard the coastguard helicopter. When we arrived at the hospital, my body temperature was around 33-degree centigrade. They cut open all my clothes and wrapped me up in a tin foil space blanket to warm me up. My eyes were still closed. Suddenly I heard the doctor talking to me in Hindi, my native language. Then I knew I was still alive.

They don’t speak Hindi in heaven, do they? Or maybe they do!

The mechanical failure that caused the gearbox break was a one in a million chance. That it resulted in so many fatalities was a terrible orchestration of events.

Friends advised me not to go back to flying. After all, the company would pension me off comfortably. But I knew money wouldn’t fill the hours.

Flying was all I had ever wanted to do. By February, I was ready to fly again.

The company insisted on psychiatric checks, however, and I resumed flying in April. I was 45 when the accident happened, and flew for another 20 years before retiring.