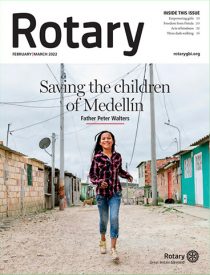

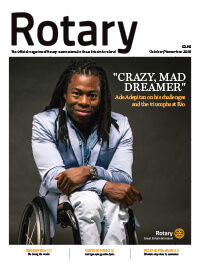

Father Peter Walters is a Catholic priest who has been part of Stratford-upon-Avon Rotary in Warwickshire for over ten years. However, to find his main line of work you would need to travel 5,000 miles across the globe to Medellín, Colombia’s second-largest city.

Medellín is set in a valley 1,500 metres up in the Andes and is the home of around four million people. The city is surrounded by shanty-towns clinging to the side of the mountains, and it is there that the divide between the rich and the poor is most evident.

Some 400 armed gangs operate in the city. Many children are forced to work in the heat and fumes of the Medellín streets – putting them directly at risk to the threat of drugs, crime, and prostitution.

Listen to this article

In the middle of all chaos is Casa Walsingham, a house that has become a place of hope for such marginalised children; and where you will find Father Peter.

Although Father Peter is not at all the sort of person you would expect to be working in the streets of Medellín, over the last 28 years he has helped thousands of street-children and other marginalised youngsters with his charity Let The Children Live!

He has no plans to leave any time soon, but explained: “I love living in Colombia. I love the people, and I love working with the children.

Father Peter Walters posing with some recent graduates from Casa Walsingham.

“Nowadays, other members of my team do most of the work in the street. I am mostly involved in the fund-raising and the planning of new programmes.

“As long as God gives me the energy, I will carry on.”

And to think, this remarkable journey all started with a holiday.

In 1982, Peter Walters was a 27-year-old theology student who saw an advert for a flight to Colombia at a particularly good price.

He reflected: “For a long time I had been intrigued by South America and hoped one day I’d be able to go over there, but this was for a holiday and not to end up living there!”

Father Peter flew to Cartagena on Colombia’s Caribbean coast for a holiday when he had a problem with his ticket.

“This meant that I was going to be stuck in Colombia for longer than my money could last, and I was reduced to eating once every other day.”

It was on one of his non-eating days when Father Peter had a fateful encounter with a group of street children who at first saw Peter as a typical foreign tourist able to give them some food or money.

“When they found I did not have any money to give them, they were very amused because they’d never met a poor foreigner before.

We would go out early in the morning looking for children, some as young as six, who’d been spending the night sleeping under bridges or on the pavements.”

“As I got to know them, I became increasingly concerned about the way they were having to live and how they were treated.”

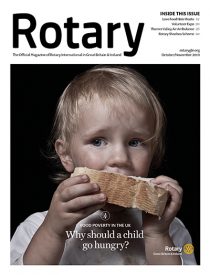

Such was the nature of their lives, that these children were tagged ‘The Disposable Ones’.

“We have disposable nappies, disposable cups and plates – things we use and chuck away. We don’t think of people being disposable, let alone children being disposable: yet, in those days, some people considered the street-children to be hardly human.

“In the streets, these children often got caught up in drugs, crime and prostitution, so they were often seen as a menace to society. In those days there were sometimes lethal outbreaks of what was called ‘social cleansing’. People who were considered undesirable – prostitutes, drug addicts, street kids – were ‘cleansed’ from the streets.”

Appalled by what he had seen and heard, Father Peter set out to find the Archbishop of the city where he was staying, to see if he could help his new friends.

Archbishop Rubén Isaza shared Peter’s concerns about the street-children and, after several meetings, gave the young Briton a piece of advice that would change his life for ever.

“In the end, he said ‘the Church is very committed to helping children like the ones you’ve got to know, but maybe God is calling you to do something to help them.’ So then I was hooked.”

Medellín is set in a valley 1,500 metres up in the Andes and is the home of around four million people.

Father Peter returned to Colombia every year to spend his holidays working for the street-children as a volunteer with the Salesian priests at Ciudad Don Bosco in Medellín. He made Medellín his base because this was where the violence was worst, and the need greatest.

He said: “We would go out early in the morning looking for children, some as young as six, who’d been spending the night sleeping under bridges or on the pavements.

“We brought them something to eat and drink, and invited them to a centre where they could spend the day. Those who accepted that invitation often ended up leaving the street and going into residential care.”

In 1988, Peter was ordained as an Anglican priest, and founded the charity Let The Children Live! whilst working at the Anglican Shrine in Walsingham, Norfolk.

But, as the violence in Colombia grew worse, he found it harder to leave the street-children, so in 1994 went out to live in Medellín, adopted the Catholic faith, and was ordained as a Catholic priest the following year.

He then started a Colombian charity to run projects and with funds raised in Great Britain and Ireland, he has been able to open two sanctuaries for the children Casa Walsingham and Casa Bannatyne.

Casa Walsingham is a day-centre for street-children and other marginalised youngsters, such those with special educational needs, along with under-age mothers and their babies.

A variety of groups and programmes operate there. The children can have

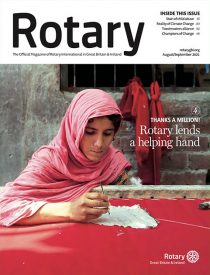

Many children are forced to live and work in the heat and fumes of the Medellín streets – putting them directly at risk to the threat of drugs, crime, and prostitution.

a healthy meal, and are supported by teachers and psychologists.

They also have a chance to play games and enjoy being children once again.

Casa Bannatyne is a residential home initially set up for children needing long-term care. However, rising costs eventually forced the charity to cease admitting new residents. When the youngsters who were living there had reached adulthood, the house became the base of Cor Videns, the charity’s choir, which Father Peter started to give a voice to children who are so often ignored, and whose cries go unheard.

Over the years, some of the children helped by Let The Children Live! have gone on to obtain professional qualifications.

These include several nurses, an industrial engineer, an orchestral conductor, a psychologist and a doctor.

But as Father Peter says: “The ones I’m proudest of all are those who, despite having an exceedingly difficult childhood, have grown up to become loving and responsible parents.

“They are trying to give their children a better start than they had. If that happens, and we have broken the cycle of an abused or abandoned child becoming an abusive or abandoning adult, then we have achieved something worthwhile.”

Father Peter considers his children to be the ultimate victims of the drugs trade. It is money spent on cocaine and heroin which keeps that trade going, fuelling corruption and violence which has afflicted Colombia for so long.

Although the murder-rate in Medellín has decreased significantly since the 1990s, the underlying problems of poverty, crime and family break-up that make children take to the streets remain unsolved.

The ones I’m proudest of all are those who, despite having an exceedingly difficult childhood, have grown up to become loving and responsible parents.”

“The authorities in Medellín claim that there is no longer a street-children problem in the city.

“But this is because the children who are found living in the street are often confined in a special rehabilitation unit at the city’s mental hospital. Children who do not want to be caught keep out of sight, so their plight is less visible.”

Lockdowns imposed in Colombia to control COVID-19 prevented children from going to school, and their parents from going to work. The situation was especially difficult for some 90,000 Venezuelan refugees who had fled to Medellín.

“During the lockdowns, these families could not work, so they had no income.

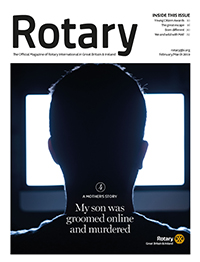

A classroom at Casa Walsingham where children can be safe from the streets and receive a good education.

We ended up sustaining more than 1,200 people with food parcels for about eight months.”

Without the help of Let The Children Live! the future of hundreds of marginalised children in Medellín would be very bleak. But, like all charities, Father Peter’s organisation needs funds to keep doing its vital work.

He explained: “In these difficult times, the support of individual Rotary clubs for small but very efficient charities like Let The Children Live! can be a tremendous help.

“No one is going to solve the problem of street-children on a worldwide basis any time soon, but supporting small charities like ours in different parts of the world can save and transform children’s lives.

“That’s what Rotary does so well. It encourages small initiatives that make a big difference to individual human lives.”

To find out more about Let The Children Live! head over to their website.