UNICEF was originally called United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund and became a permanent part of the United Nations in 1953. Wherever there are children in the world at risk from violence, exploitation and abuse, disease, hunger and malnutrition, war and conflict, and disaster, UNICEF is present with aid.

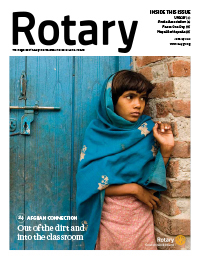

This could not be more so than in Afghanistan and we felt as this edition was featuring that country; we should talk to the main people from UNICEF who are deployed there.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Dr Balaji the Deputy Representative of UNICEF in Afghanistan and Peter Daglish, UNICEF polio team lead, who is now based in New York.

I spoke first with Dr Balaji about the work in Afghanistan and the factors surrounding UNICEF’s effort. We started with an outline of the programme, which although continuing, was reviewed and implemented in June of last year. This is a five year initiative based on six programmes focussing on health, nutrition, education, water and sanitation, child protection, and social inclusion.

The programmes are backed by $650million with contingencies for what Dr Balaji called ‘unpredicted natural disasters’ such as flooding, landslides and drought, for which $150million is set aside. Total aid from UNICEF over the five years is therefore around $800million, some of which will never be used. Dr Balaji explains, “Afghanistan is recognised as a humanitarian crisis which is a result of man-made disasters and not natural causes.”

The main office of UNICEF is based in Kabul and they have five zone offices including Kabul in Mazar-e-Sharif, Herat, Jalalabad and Kandahar. Each office has two programme staff, one of which is a local and is usually what is called an access negotiator.

The access negotiators work with the local communities where they try to convince the local mullahs that the children require educating. Community schools are set up and the children taught by females who must not as Dr Balaji says “they must not push one ideology or the other because if they teach what the government does, for instance, they could be abducted or even killed”

The total number of international and national staff in Afghanistan is 360.

They must not push one ideology or the other because if they teach what the government does, for instance, they could be abducted or even killed.”

We spoke about maternal and infant mortality and Dr Balaji informed me that because of interventions infant mortality has now reduced to 99 in 1000 children under five, which from a western viewpoint is still quite high. One of UNICEF’s priorities is to educate girls to the same level as boys and the security access negotiators spend a lot of time identifying and speaking with village elders to allow the girls an education.

When this happens an accelerated teaching programme is put in place covering six grades in three years.

In discussing the security situation, Dr Balaji referred to AGE’s. When I asked what these were, he said, “there are so many factions in this country that we do not brand them. We do not wish to be any part of the conflict so we term them Anti Government Entities (AGE’s)”. We also touched on the religious aspect in the country but this was not a factor in their work.

We covered many aspects of the agency’s work in Afghanistan and came on to their work with internationally displaced persons (IDP’s), which seems to be an ongoing challenge especially on the border with Pakistan.

The north east border with Pakistan seems to be quite a challenge and came up in my discussions with Peter Daglish, UNICEF polio team lead. We did discuss Afghanistan and the challenges there but Peter was very upbeat about the progress of the polio campaign in both countries. He encourages everyone to, “stay focussed and help to finish the job, since it is very easy to become cynical about the exercise, but it is essential to cease the moment.”

He cited India as a good example of what could be done: “Who would have thought a few years ago that India would be declared polio free so soon?” he said. Peter had been back to Afghanistan just before we spoke and had visited Kandahar and says he was struck by the change in activity at the airport since the alliance had left. “It is important not to shift attention from Afghanistan. The progress there is so fragile so we need to maintain the effort.”

Both Peter and Dr Balaji lavished wholesome praise on the part Rotary has played in the eradication of polio worldwide. They emphasised that although the last few years have been tough there is no doubt that the future will present no less a challenge.

These two very senior people with first-hand experience on the ground thanked Rotarians for their massive efforts and urged them to maintain the effort for children to be born into a polio free world.