The headline on the facing page are the words of Sir Nicholas ‘Nicky’ Winton, an amazing man who saved hundreds of lives during World War Two – and who was also a Rotarian.

Nicky is also the subject of the film ‘One Life’ which was released in UK cinemas in January, starring Sir Anthony Hopkins and Helena Bonham Carter.

‘One Life’ tells the true story of the young London broker who, in the months leading up to World War Two, rescued 669 children from the Nazis.

Indeed, in a pivotal scene, Sir Anthony who plays Nicky, is pictured at the BBC studios where details of his heroic work were broadcast for the first time. He is pictured on screen wearing a Rotary tie and pin as a proud member of Maidenhead Rotary Club in Berkshire. Nicky died in 2015 aged 106.

In December 1938 Nicky visited Prague. There he found families who had fled Germany and Austria, who were living in desperate conditions with little or no shelter and food, and under threat of Nazi invasion. He realised it was a race against time. How many children could he and the team rescue before the borders closed?

Listen to this article

The film fasts forward 50 years later to that BBC studio It is 1988 and Nicky is haunted by the fate of the children he was unable to bring to safety in England; blaming himself for not doing more.

It is then that the BBC television show ‘That’s Life’ surprises him by introducing some of the surviving children – now adults – and only then does come to terms with the guilt and grief he had carried for five decades.

Producers Emile Sherman and Iain Canning first discussed Nicholas Winton’s story when they co-founded See-Saw Films 15 years ago, having come across the ‘That’s Life!’ clip.

Emile Sherman says: “We knew the first step was to meet Nicky who we could tell from the television clip was going to be a very humble man.”

Iain Canning continues: “We were very lucky to have had the opportunity to meet Nicky before he passed away. He was the most modest, generous human being, who felt the film should not glorify him, but celebrate how the most ordinary of people can make a huge impact.”

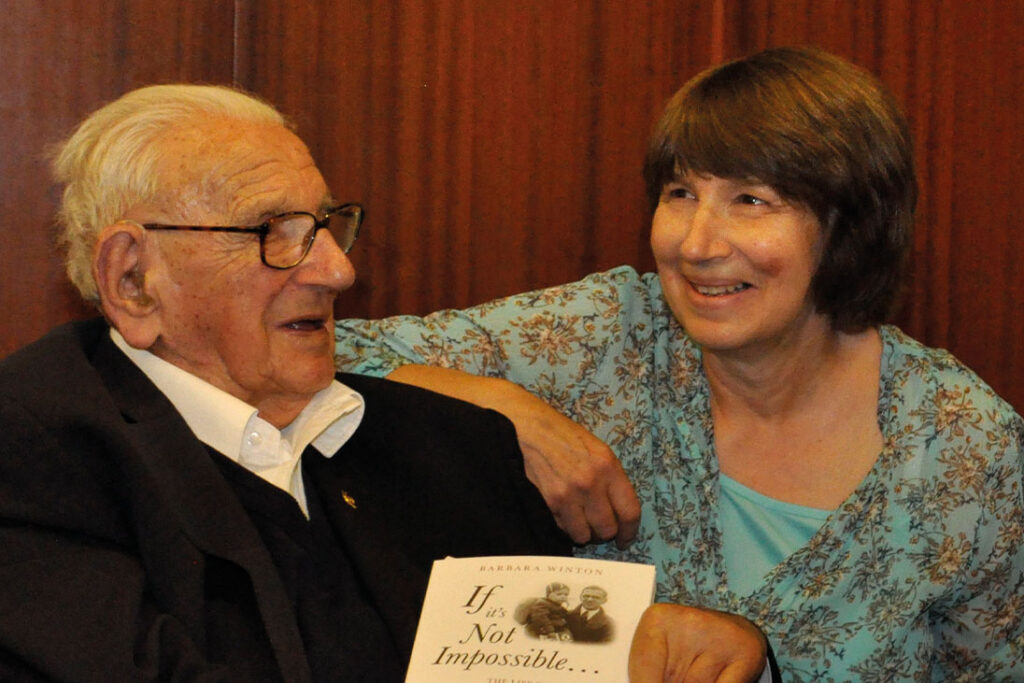

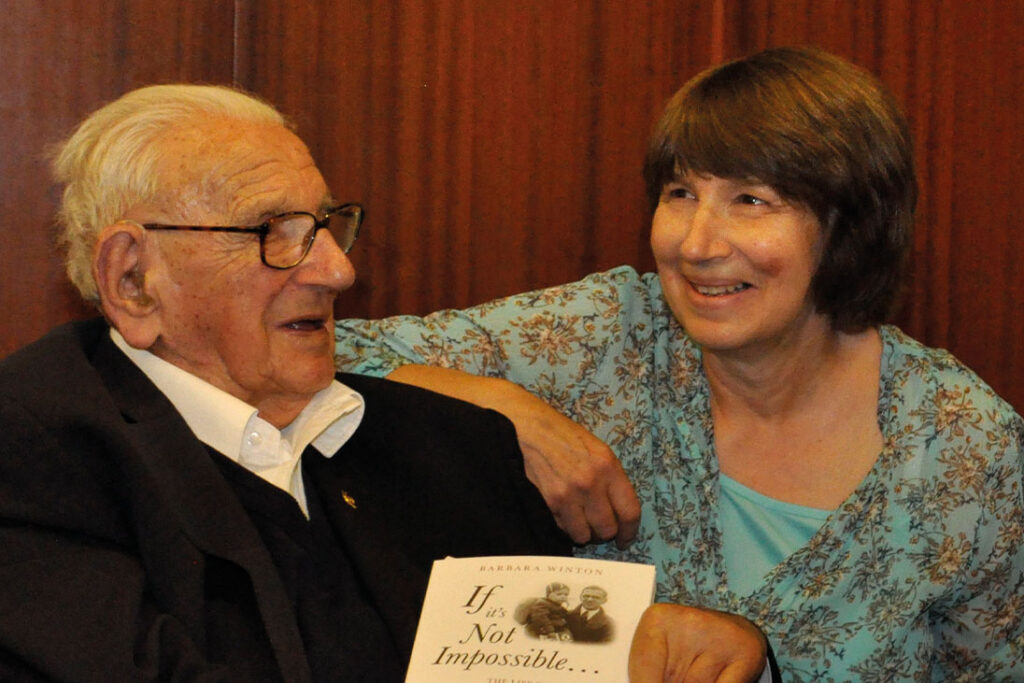

With the blessing of Nicky’s daughter Barbara Winton, See-Saw approached screenwriter Lucinda Coxon to adapt Barbara’s book ‘If It’s Not Impossible’.

Collaborating with Barbara, who sadly died in 2022 during the making of the film, the screenwriting team gained access to Nicky’s archives and letters, as well as her book about her father.

Sir Nicholas Winton and Barbara Winton pictured during the release of Barbara’s book ‘If It’s Not Impossible’

Barbara was a familiar face at Rotary District Conferences who wrote an article in Rotary magazine in 2019 that told her father’s story.

“My father had a thick skin to get his projects done and it worked,” recalled Barbara in the article.

“In terms of this project, my father felt he had failed. They had 5,000 names on this list and only 669 were saved. But 50 years later when the story came out and he met some of his children, we discovered there were about 7,000 people alive because of what he had achieved.”

See-Saw Films producer, Joanna Laurie, admits the main challenge of developing the film was doing the thing that Nicky found most difficult: singling himself out.

She explains: “He really didn’t see himself as a hero, so our challenge was telling this extraordinary story while honouring his humility. The title of this film, ‘One Life’, could mean different things to different people but I think the movie asks us all to reflect, as Nicky did, about our choices as individuals and as a community.”

Director James Hawes says this attitude was typical of the generations who faced the inhumanity of war.

“We have to put ourselves in the minds of that generation; you didn’t speak about the war. I’m sure many people know grandparents and great-grandparents who have memories from the war and they don’t talk about it because it was too awful.”

Barbara Winton’s book was also an essential resource for the cast.

Explaining how she got a sense of Babi, Nicky’s mother and Barbara’s grandmother, Helena Bonham Carter explains: “Barbara was named after Babi. I was very lucky to speak to Barbara, to have her perspective as a granddaughter as well, but Babi was also in her book.”

Johnny Flynn, in his role of the young Nicky Winton, adds: “Barbara’s book was an essential piece of research for me, along with several other books.”

The film itself bridges two time periods – 1938 and 1988.

One of the elements the screenplay needed to address was Nicky’s own family history, and how it informed him and his choices.

Nick Drake, who wrote the screenplay with Lucinda Coxon, notes: “Nicky’s Jewish ancestry meant he was alert to what it meant to be an émigré, from the rise of Nazism in Europe. He was ashamed by the Allies’ betrayal of the Czech people in the Munich Agreement.

“Nicky saw the consequences of that agreement in human terms and these appalling camps where refugees from Germany, Austria and the Sudetenland were living in intolerable conditions.

“He was motivated by the reality he saw in front of him and decided to do something about it.”

In distilling the war era story, Sir Anthony Hopkins – who plays the older Nicholas Winton – says: “It’s about several people not just one man – saving the lives of children who are about to be consumed into the gas chambers and furnaces of Auschwitz, Treblinka and Belsen.”

It was Barbara Winton’s wish that Sir Anthony Hopkins, the winner of six Academy Awards, should play her father.

Producer Iain Canning reveals: “When Barbara read the first draft of the script she called us to say that Anthony Hopkins would be perfect for the role, which we of course agreed with, but left us with a challenge because it was beyond our wildest dreams that Anthony Hopkins would read the script and want to play Nicky.

“But incredibly, he did, and it was magical for all of us to know we had an extraordinary actor playing a man who was such an inspirational humanitarian.”

Sir Anthony Hopkins on the set of One Life with Director James Hawes. © Warner Bros.

The film was shot in Prague and England, working across two time periods and working with two crews in two languages.

It was important to shoot the film in Prague, using the authentic Prague locations, even filming on the same station platform from where the children said goodbye to their families and departed for England more than 80 years ago.

A bronze statue of Nicky with two small children and a suitcase marks the historical spot at the end of the same platform. It is estimated that there are about 7,000 people alive today because of the Prague rescue.

Describing the challenges Nicky and the team faced to bring the children safely to the UK and find host families, Director James Hawes explains, “There was a belief in the UK they weren’t at risk; a lot of people saying, ‘it’s fine, there’s no issue, they’re in Prague, they’re not in Austria or Germany’.

“Another challenge was British bureaucracy and xenophobia: the newspapers and politicians saying, ‘We’re a small, crowded island. There’s no place for more people here.’

“Nicky had to fight that prejudice; raising the public consciousness, writing articles – way before the internet or broadcast news, where he had to somehow get the message out there through the newspapers, word of mouth, institutions, letters, so enough people would support him.”

The tragedy of the final train, the ninth train to leave Prague in September 1939 was the pain which Nicky could not speak about when 251 children were loaded onto the train at Prague Station, ready to leave for England.

But that was the very day war was declared and the borders were closed.

Helena Bonham Carter appears in the film as Babi, Sir Nicholas Winton’s mother. © Warner Bros.

The Nazis pulled the children off the train. As far as is known, all but four of those children died in the concentration camps.

For the emotional ‘That’s Life’ scene, producers invited Nicky’s children and their relatives to be part of the film as supporting artists, with Sir Anthony Hopkins only told of their identity on the day of the shoot.

Anthony Hopkins recalls: “It was like a kick in the chest when all the descendants came in. It was hard to try not to be sentimental, but it was very moving.”

Nicky was a conduit to the children’s past, most of whom had lost their parents. Director James Hawes explains: “He was a lightning rod back to the roots of who they were.

“At that moment in the film, Esther Rantzen says ‘anybody who owes their life to Nicky Winton, please stand up,’ and our supporting artists, the relatives, do stand up because they also owe their lives to that man. Those people would not exist, but for him. There was not a dry eye on the set floor.”

As for Sir Anthony Hopkins, the crew said he revelled in the production, loving the challenge of telling such an amazing story. He adds: “I only hope this will send a message lest we forget, because we forget so quickly.”

Watch the trailer for One Life on YouTube here.