Despite evolving perspectives, those not fighting on the front lines struggled to comprehend the conflict.

A Rotary member from England, visiting a strategic bridge in Edinburgh, marvelled that “the sight of sentries, barbed wire and loop-holed sand bag protections brought the war much nearer than we realise it in Manchester, as also did the inspiring sight of the [Royal Navy’s] fleet” anchored in the Firth of Forth.

On July 1st 1916, in north-west France along the Somme River, British troops stormed the entrenched German army.

By day’s end, they had suffered 57,470 casualties, including 19,240 soldiers dead from their wounds.

Winston Churchill called it “the greatest loss and slaughter sustained in a single day in the whole history of the British Army.”

Fighting continued along the Somme for another 140 days, engaging about 3.5 million men from 25 countries.

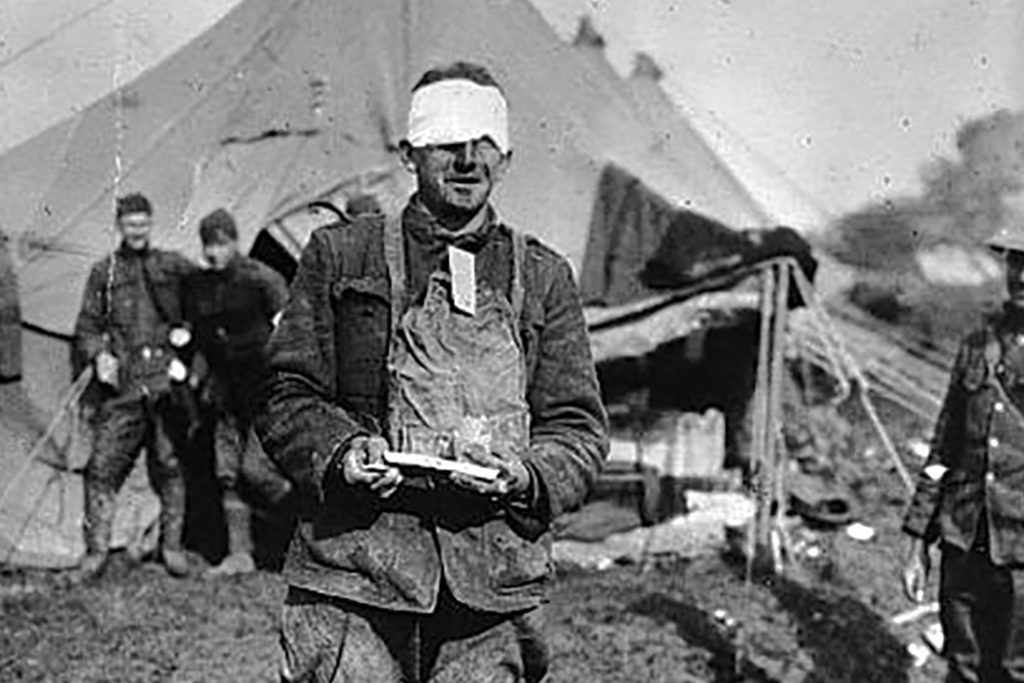

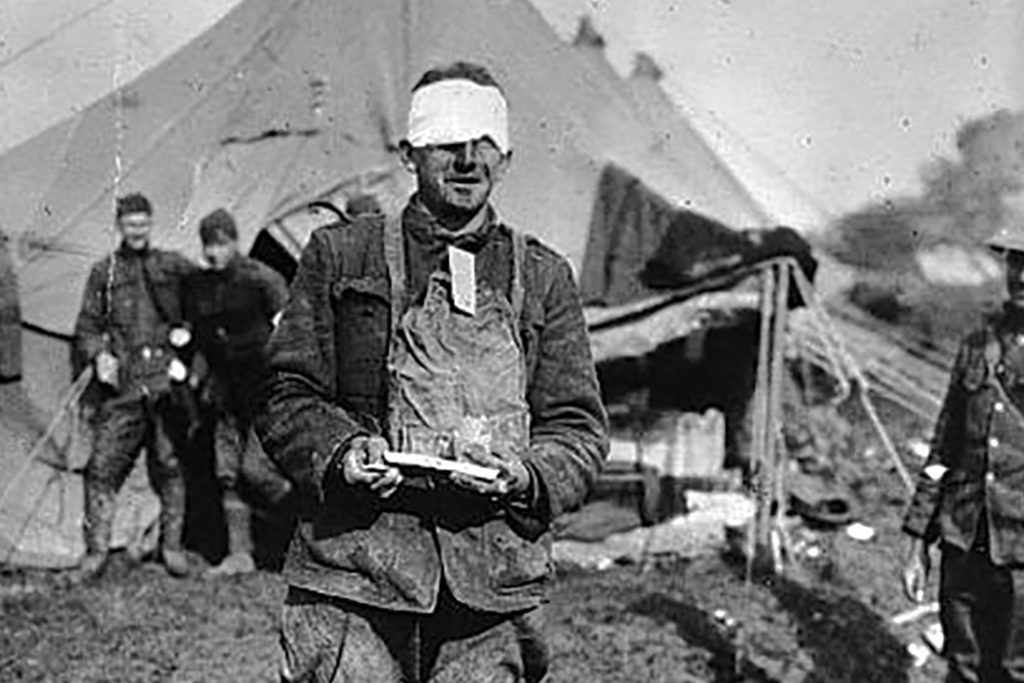

An American with chocolate given by the Red Cross on the Meuse-Argonne battlefield.

By mid-November, when winter weather brought fighting to a halt, British forces, which included troops from Australia, Canada, India, Ireland, and Scotland, had suffered about 420,000 casualties; the German army sustained at least 430,000, and France, 204,000.

The maddeningly snail-paced nature of the fighting meant the daily advance or retreat of armies was often calculated in inches and feet and yards.

In November 1916, readers of The Rotarian got an unexpected glimpse into the trenches along the Somme.

Weeks earlier, George Brigden, a future president of Toronto Rotary, had received a letter from a Canadian lieutenant named F.G. Diver.

Dated September 11th, it began: “You will no doubt be quite surprised to receive a letter from me but I felt that I wanted in some way to show my appreciation to you for putting me into the Rotary Club and to let you know that even in the front line trenches away over here in France that I have felt its influence.”

Diver went on to explain that, while in England with a Canadian division formed in Ontario, he had been “one of the lucky” officers ordered to proceed immediately to France, where he joined the 87th Battalion, a Montreal unit known as the Canadian Grenadier Guards.

Not knowing any of the officers, he had found it “pretty hard … to break in to their little circle.”

During a lull in the fighting, he stepped into another officer’s dugout “to have a smoke and incidentally see if he had anything on the hip, as it gets mighty chilly around here between four and five in the morning.”

That other officer turned out to be Major H. LeRoy Shaw, a founding member and former president of Montreal Rotary.

What’s more, as Diver learned, two other officers in the 87th were also Rotary members: Majors Irving P. Rexford and John N. Lewis.

“From that night on,” explained Diver, “it has made quite some difference for me, for, although I am not yet one of their happy little family, I am a whole lot nearer than I would have been if it had not been for good old Rotary.”

Before signing off “Yours Rotarily,” Diver described the “great life” in the trenches.

“Live like so many rats in the earth and, like rats, never change your clothes. … But with all the inconveniences there is something that makes you glad you came.”

A little after noon on October 21st, during fighting east of the Ancre River, a tributary of the Somme, the Canadian Grenadier Guards seized a German position called Regina Trench. Leading his platoon, Diver died in the attack.

Rotary clubs contributed funds to buy ambulances, like these Red Cross vehicles- 1917

Four weeks later and less than a mile north from where Diver had fallen, Lewis met the same fate.

Born in Tennessee in 1874 and a graduate of the universities of Chicago and Heidelberg, Lewis had worked for a Chicago newspaper before moving on to become editor of the Montreal Star.

Second in command, behind Shaw, of the 87th’s No. 1 Company, he had won the Distinguished Service Order for his heroism in the attack on Regina Trench.

A little before dawn on 18 November, as a driving rain turned to snow, the Grenadier Guards climbed from flooded trenches and slogged under enemy fire across a muddy no man’s land to yet another German bulwark, this one called Desire Trench.

By 8am, the Guards had captured the position, and Lewis was dying, or perhaps already dead.

His obituary in the Star noted that Lewis, a founder of the local Boys’ Club, had, in both Chicago and Montreal, contributed generously “to charitable organizations having the care and upliftment of children as their special concern.”

In Lewis’ memory, Montreal Rotary raised $10,000 to erect a building at the Shawbridge Boys’ Farm in Quebec with a brass plaque inscribed, “Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.” (Home to 30 boys, the two-story brick Lewis Memorial Cottage stood until the 1960s.)

As for Shaw and Rexford, they survived the war and returned to Montreal, Shaw to pursue his pre-war insurance career (and his passion for curling) and Rexford to assume the presidency of the club, where, in 1929, he led a successful campaign to raise more than $250,000 for the Boys’ Home Fund.

Don’t miss!

Historian David Fowler marks 100 years of the Armistice in December’s issue of the Rotary GBI magazine.