On November 7th, 1916, after campaigning under the slogan “He kept us out of war,” Woodrow Wilson won a second term as American president.

On April 2nd, 1917, four weeks after his inauguration, he addressed a special session of Congress and asked for a declaration of war against Germany.

Within days, the House and Senate gave Wilson what he wanted.

An honorary member of several Rotary clubs, Wilson was later eulogized by The Rotarian as “an apostle of peace.”

But after the Germans rejected his attempts to negotiate an end to the war, resuming unrestricted submarine warfare and hatching a plan to lure Mexico into the conflict by promising to help it recover its former territory in the American Southwest, Wilson had had enough.

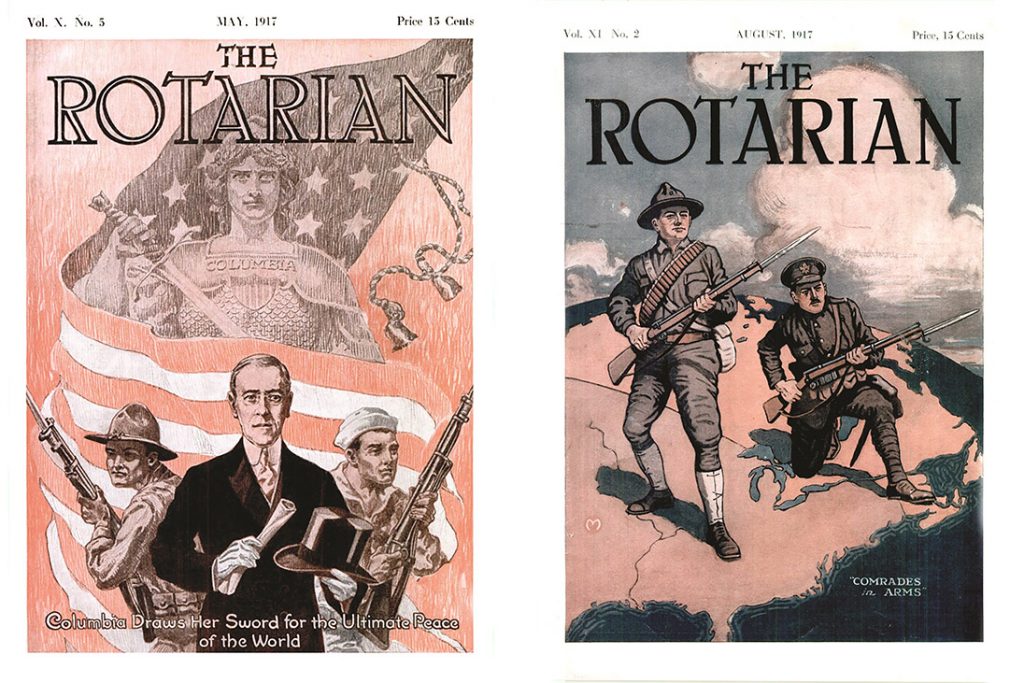

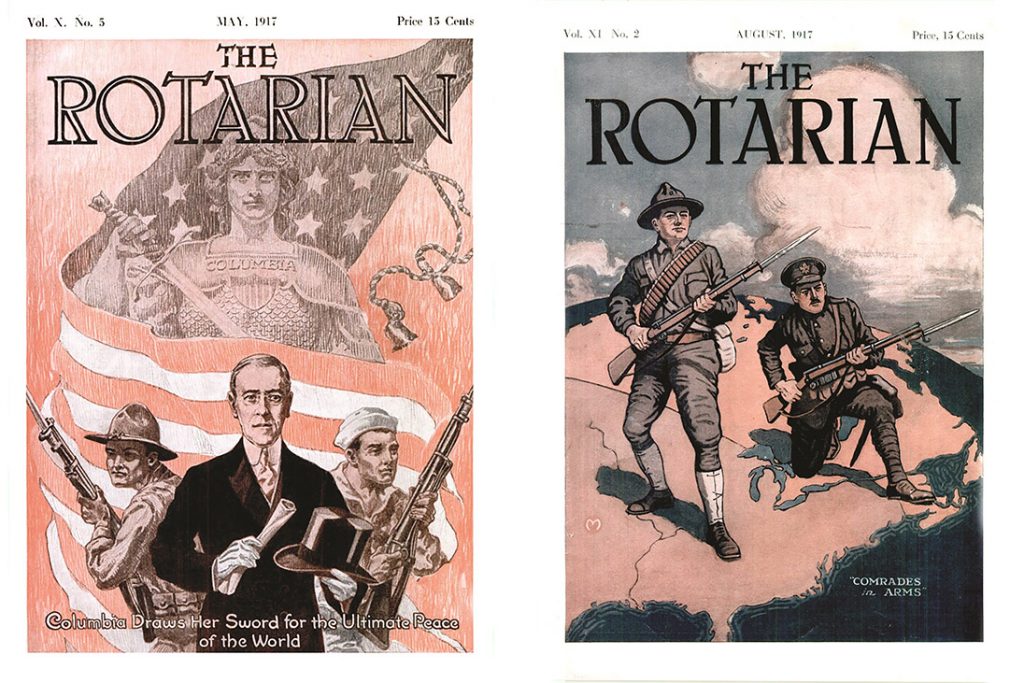

Covers of The Rotarian published in 1917.

The Rotarian supported the president.

“In his call to the democrats of the world,” it editorialized in May, “President Wilson has placed before them, in a clear light, the Rotary principle of service above self — service for the whole world — above [the] self-interest of any nation.”

In the same issue, a full-page advertisement festooned with American flags and bearing the boldface headline “WAR” promised that the upcoming annual convention would “give additional support to the President of the United States, by the most wonderful demonstration of business and professional men ever assembled at a Convention.

“Don’t fail to come to Atlanta, where International Rotary History will write its greatest chapter.”

Too ill to attend the convention, Paul Harris sent a message to be read there, in which he extolled Wilson — “the ideal of American citizenship” — and turned an optimistic eye toward the potential benefit of war.

“These are mighty days, days of incomparable opportunity — of opportunity undreamed,” he wrote.

“Off with the useless old, on with the useful new. There will never be a better chance than now.

“Humanity must rise triumphant from this vale of sorrow, ennobled by its suffering.”

With all this came a decided change in the tenor of this magazine.

Gone was the monthly News of the Clubs column, replaced by updates about “Clubs Busy at Patriotic Tasks” and “War Service Work by Rotary Clubs.”

Rotary members pitched in to pay for ambulances and other martial necessities, and they contended to outdo one another with their contributions.

Members of Utica Rotary, New York, purchased $330,000 in liberty bonds as part of its ‘Win the War’ effort.

Of course, The Rotarian had carried reports of such civic projects, especially from parts of the British Empire, all along.

During the summer of 1915, for instance, Belfast Rotary generously contributed to a local ambulance fund.

That autumn, Rotary members in Dublin “spent a considerable portion of [their] energies in entertaining wounded soldiers.”

And as the year ended, members in Hamilton, Ontario, staged “many fetes and other public affairs … to raise money for the needs of soldiers at the front.”

In his call to the democrats of the world, President Wilson has placed before them, in a clear light, the Rotary principle of service above self – service for the whole world – above [the] self-interest of any nation.”

In September 1917, on War Department stationery, Raymond B. Fosdick, chairman of the commission on training camp activities, wrote a letter of appreciation to Chesley Perry, editor of The Rotarian and Rotary’s first general secretary (though that specific title didn’t exist yet).

“I am so impressed with what your organisation has done that I have brought it to the attention of both the Secretary of War and the President,” Fosdick wrote.

President Wilson followed up with his own letter to Perry in which he acknowledged that “the service rendered by your organisation in this time of national stress has been very great, and I feel that you are making a genuine contribution to the cause which we all have so much at heart.”

The names of distinguished Americans began to appear in the magazine alongside wartime messages.

Major General Leonard Wood wrote about “The New American Army.”

U.S. Food Commissioner and future President Herbert Hoover preached the “gospel of the clean plate,” outlining ways to save meat, milk, fats, sugar, and fuel.

“The way to win,” he said, “is to stop wasting.”

Walter Camp, the ‘father of American football’ laid out his idea for a Senior Service Corps that would allow men over age 45 “to become efficient patriots.”

War-themed poems and declamations also became a regular feature of the magazine, literary lucubrations titled “For France!” or “The Age-Long Battle” or “The Kid Has Gone to the Colors.”

They aimed to uplift, but there were hints of despair.

In December, Philip R. Kellar, managing editor of The Rotarian, offered “The Message of This Christmas.”

It began:

O warring, biting, hate-filled world!

O world all bleared and sodden with the blood

Of countless victims of the wrath of war …

Where murder, rapine, lust, deceit and lies

Have been unleashed to prey, unchecked, on man!

The poem’s final stanza sounded a note of hope, but could not dispel the gloom.

Like the rest of the country, Kellar was awakening to the carnage that was still to come.

Don’t miss!

Historian David Fowler marks 100 years of the Armistice in December’s issue of the Rotary GBI magazine.